PRODUCTIVITY NORMS AND HOW TO USE THEM

“We used standard norms to estimate productivity and activity durations, but the project is still behind schedule.” You probably have heard that before. Yes, you have used norms to develop estimates and plan the project. You have resourced the project as planned. Why is the project behind schedule?

The answer lies in the norms. An average estimator or planning engineer does not know what the norms represent. I have mentioned in a previous essay, my encounter with a misunderstood and misapplied norm. It was the case of a contractor’s planning engineer who had used standard norms to estimate the duration for excavation of equipment foundation at a brownfield project site. The project was still significantly behind schedule. Upon review of the contractor’s report I discovered that they had deployed much more resources than was planned. I became curious. Upon interview of the planning engineer I discovered that the crew was delivering only 30% of the planned productivity based on company norms.

Obviously, the planning engineer did not understand what the norms represented.

The following questions should be asked before making use of either commercially available productivity data or even in-house norms:

- What does the norm represent?

- What are the bases and assumptions?

- Are they applicable to my situation?

- What can I do to adapt them to my situation?

I will attempt to answer each of these questions using a productivity data from one of the leading engineering consultants in the world, to illustrate the point.

- What does the norm represent?

The company’s Estimation Manual specifies 250 man-hours for the installation of a 14 ton/hour [metric] steam boiler. But what does ‘installation’ mean? According to the manual, it includes receiving, offloading, retrieval, hauling, rigging to position, shimming to elevation, leveling, aligning, lubricating, bumping for rotation checks and installing guards. It also includes field engineering to establish center lines and benchmarks, as well as scaffolding. It excludes electrical, pipe hook-up and installation of refractories.

An uninformed planning engineer or estimator would simply pick that number and apply it to the whole installation process, and blame construction for not working hard!

- What are the bases and assumptions?

What did they consider in developing the norm? For the example above, assumptions include:

- All work performed during daylight hours (allowance required for night work)

- Availability of adequately skilled staff (Note: Adequately skilled, not just staff)

- Work is normal 40-hour work week – 8×5 or 10×4. Longer hours may result in overtime deterioration.

- Maximum distance from storage/ laydown area – 150m

- Minimum work area per person – 33 square meters (allowance required for confined space or crowded work area)

- Maximum work height of 6m above floor/ grade

- Mild climate

- Site is level, dry, with adequate temporary facilities

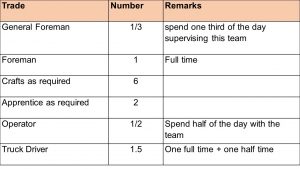

A major point to consider is the composition of the crew. In the case in hand, the crew is composed as follows:

I will not forget an experience I had many years ago, in the Gulf of Guinea. I had led a project team to replace a flare line for Total. The community leaders insisted that we employ fitters from among their people. They then presented us the ‘fitters’ which we employed. Some of them could not identify a spanner! Again, the skill level of each of the team members is critical to the application of the norms. If there is a certification for the craft, then that might be an easy basis for comparison.

- Are they applicable to my situation?

By examining items 1 and 2 above one should be able to determine whether it can be applied as is or adjustments need to be made.

For example, the manual states that the norms are for projects in Canada and US. That alone should raise red flags in the application.

- What can I do to adapt it to my situation?

One needs to compare his environment with the US and possibly develop a correlation or multiplication factor to adapt to his environment. In doing so he needs to make allowance for differences in skill level, work culture, efficiency, morale, etc.

It should now be obvious why most projects are delayed even when we use ‘norms’. This does not only apply to commercial norms but even in-house norms need to be applied with care, on a case by case basis. It is impossible to develop in-house norms that would cover every conceivable work situation. Therefore, it is the duty of the planning engineer or estimator to carefully review the bases of the norms vis-à-vis the task in hand, and then consider what adjustments might be necessary in order to make them applicable.

Just lifting the data from the handbook or database and applying to the project is the cause of many project delays.